Thermal Priming Trials with SFU & the Pacific Salmon Foundation

TLDR

West Coast Kelp is collaborating with Simon Fraser University and the Pacific Salmon Foundation to test whether young kelp can be “primed” to better tolerate future heatwaves. The project uses West Coast Kelp’s bioreactors to expose microscopic kelp life stages to short bursts of heat, studying how they respond at the genetic level. This process, called thermal priming, could help kelp “remember” stress and become more resilient as oceans warm. If successful, it may open new ways to prepare seedstock for restoration and cultivation in a changing climate.

Can young kelp be “primed” to withstand warmer water and future heatwaves?

That’s the question behind a new collaboration between Simon Fraser University, the Pacific Salmon Foundation, and West Coast Kelp. In this experiment, gametophytes (the microscopic life stage of kelp) are exposed to elevated temperatures in a process known as thermal priming. The idea is simple but powerful: by briefly stressing young kelp under controlled conditions, researchers may help them build lasting resilience to future warming events.

Across the Pacific coast, warming oceans and marine heatwaves have pushed kelp forests to their limits. These underwater forests anchor marine biodiversity, buffer shorelines, and sustain fisheries, yet their sensitivity to temperature stress makes them vulnerable to collapse. Restoring them is one of the most promising ways to support ocean resilience, but success increasingly depends on understanding how kelp itself can adapt.

The biology behind the experiment

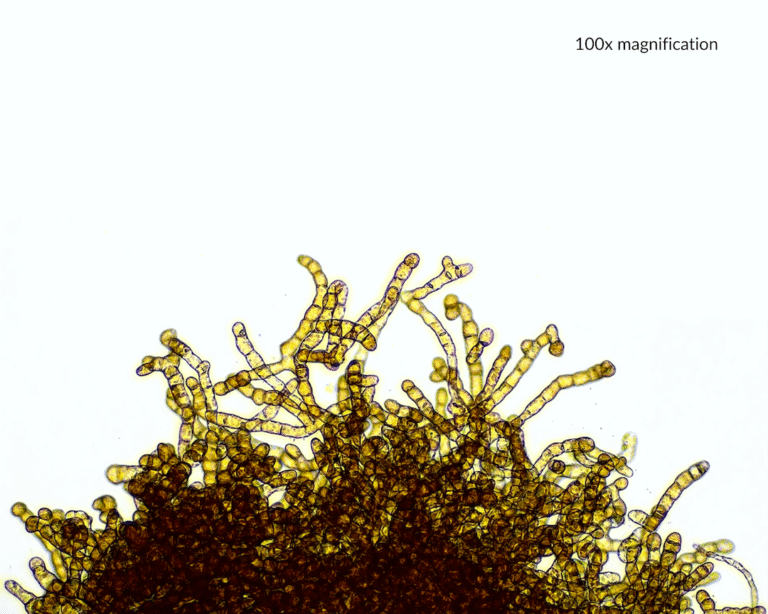

Kelp has a fascinating two-part life cycle. The large, canopy-forming plants we see underwater are just one phase, known as the sporophyte stage. Hidden from view is a much smaller stage called the gametophyte, which exists as microscopic filaments in the lab and produces eggs and sperm. Because these gametophytes can be cultured in the millions under tightly controlled conditions, they are ideal for experiments that test how kelp responds to stress.

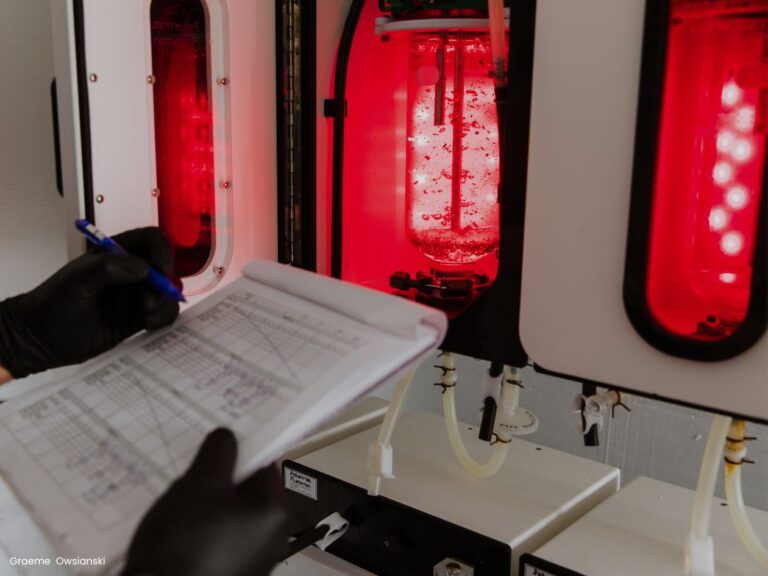

West Coast Kelp is supporting this project by cultivating the gametophytes and using its Industrial Plankton Seaweed Bioreactors to administer thermal treatments. These systems allow precise control over temperature, light, and nutrient conditions, creating a perfect environment for testing how brief pulses of heat affect kelp at its earliest stage.

Remembering stress

The concept of thermal priming is rooted in epigenetics, the study of how organisms can “remember” stress without changing their DNA. Instead of altering the genetic code, epigenetic changes act like bookmarks that turn certain genes on or off depending on the conditions an organism experiences. For kelp, that could mean activating a suite of heat-response genes that help it recover faster or survive longer the next time ocean temperatures spike.

Early research in plants and microalgae suggests that thermal priming can enhance stress tolerance well beyond the initial exposure period. If similar patterns hold true for kelp, the implications for restoration could be significant. It would mean that resilience is not fixed, it can be cultivated.

A collaboration bridging research and practice

This study combines the strengths of three organizations with complementary expertise. Researchers from Simon Fraser University bring deep knowledge of kelp biology and epigenetics. The Pacific Salmon Foundation supports applied research that strengthens the resilience of coastal ecosystems. West Coast Kelp contributes the infrastructure and operational experience to grow, manipulate, and monitor kelp in real-world conditions.

Together, these partners are testing whether insights from molecular biology can translate into practical tools for restoration and aquaculture. The work also demonstrates the growing value of collaboration between universities, NGOs, and small coastal businesses that can scale innovative science beyond the lab.

Building tools for a changing ocean

While still in its early stages, the project represents a new direction in applied restoration science, one that does not just ask how to restore kelp forests to what they were, but how to prepare them for what is coming. If thermal priming proves effective, it could become part of future seed preparation processes for restoration or cultivation, giving young kelp a physiological head start before they are deployed in the ocean.

It is an example of how investment in scientific partnerships today could unlock tomorrow’s restoration tools. As climate impacts accelerate, these proactive approaches that combine research precision with practical field experience will be key to keeping coastal ecosystems productive, diverse, and resilient.

West Coast Kelp is proud to be part of this work, helping bridge the gap between experimentation and real-world application.

Project leads: Sherryl Bisgrove (Simon Fraser University) and Liam Coleman (Pacific Salmon Foundation)

SFU team: Amnit Sokhey, Kelsey Pierce, Franknel Pabai, and Travis Lee