Why Growing Kelp on Longlines Belongs in the Restoration Toolkit

TLDR

Restoring kelp forests isn’t just about replanting what once was, it’s about rebuilding the biomass that drives their ecological benefits. Longline cultivation, a proven method from commercial farming, can rapidly produce dense kelp canopies that provide habitat, absorb carbon, and protect shorelines, all while avoiding urchin grazing. Because the gear is low-cost and easy to manage, it’s ideal for Indigenous and community-led restoration. Think of longlines as scaffolding: a temporary but powerful tool to restore function and buy time while ecosystems and policies catch up.

Why Growing Kelp on Longlines Belongs in the Restoration Toolkit?

Kelp forests shape life along North America’s Pacific coast, yet their decline is starkly visible. There are fewer canopies, fewer wild salmon, and fewer swirls of carbon-hungry fronds buffering our coasts. When we talk about bringing the lost kelp back, we often picture seedlings taking root on a reef, recreating what once was. But if the goal is to revive the ecosystem services kelp delivers, such as habitat, carbon drawdown, oxygen production, and shoreline protection, then scale matters more than strict mimicry of the past.

Why Biomass is the Bottom Line?

Every service we value from a kelp forest is proportional to the sheer mass of blades in the water column. Long-line cultivation, refined by decades of commercial farming, is simply the most efficient way to generate that biomass. In the right conditions, a single 100-metre line can grow over a metric tonne of kelp in a season. This is something more novel kelp cultivation methods, such as Green Gravel or sori-bag seeding, have yet to match.

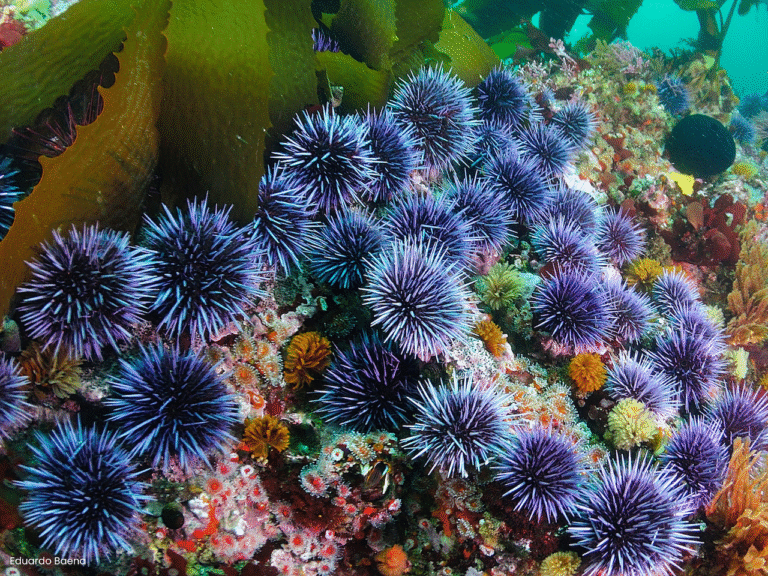

Rising Above the Urchin Challenge

Sea urchins remain the unsolved pressure point on much of our coast. Culling programs and integrated fisheries have helped at the margins, but widespread overgrazing continues. By suspending lines a few metres off the bottom, we move young kelp out of the urchins’ reach. The result is dense, three-dimensional habitat that returns quickly and reliably.

Despite growing recognition of the problem, current policies do not provide a clear or coordinated framework for addressing urchin overpopulation at scale. Without integrated action across jurisdictions, and better alignment between fisheries management and restoration objectives, many affected regions are left without practical tools for ecological intervention. In the meantime, long-line cultivation offers one of the few proven ways to sidestep the urchin barrier and restore kelp-derived ecosystem function.

Cost, Consistency, and Community Science

Long-line gear is off the shelf, deployable by small boats, and maintainable by local Guardians or fishing crews. That makes it scalable for Indigenous-led programs and community scientists who are ready to steward kelp but need methods that fit existing capacity. Lower cost per tonne of biomass also frees up limited grant dollars for monitoring, youth training, and research on the next set of challenges.

A Living Scaffold, Not a Forever Fix

Does kelp naturally grow on rope? No. But neither did salmon eggs once incubate in aluminum trays on shelves in hatcheries. Long lines should be seen as scaffolding: a temporary structure that restores function while we tackle the root causes of decline, such as warming seas, nutrient shifts, and overpopulation of sea urchins. As conditions improve, we can ease the lines out and watch natural recruitment take over. Until then, using a proven and reliable method such as long-line kelp cultivation is our most pragmatic path to rapid biomass recovery.

Kelp has always adapted to what the ocean offers. Our restoration tools must be just as flexible. Long-line cultivation lets us seed abundance now. It buys time for ecosystems and policies to heal. The underwater forests, and their residents, will thank us for it.